An excerpt from

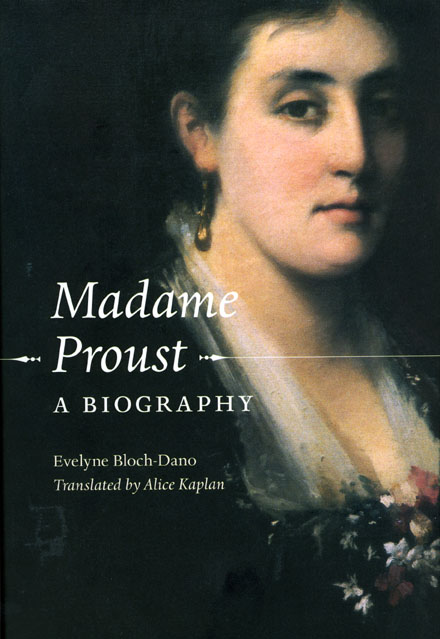

Madame Proust

A Biography

Evelyne Bloch-Dano

Translated by Alice Kaplan

The Goodnight Kiss

For the young mother Jeanne, the stages in her sons’ upbringing were well laid out. Children had their place in the life of a bourgeois family, but their situation was governed by rules and customs that went unquestioned. Indeed, the children’s development could be measured by codified benchmarks: swaddling clothes for the infants, then a gown that made changing diapers easier; bottles, then pureed baby food; around age seven, a boy began to wear short pants instead of dresses, as if to differentiate him from babies and little girls. Before that, his curls would have been cut, another important rite of passage. A boy acquired his individuality by distinguishing himself from all that was feminine. Jeanne saw these stages as progress. Yet her optimism was occasionally mixed with the feeling that she was somehow losing her babies, that in growing older her sons were growing away from her. And while Robert went through his first stages energetically, hastening, like many younger brothers, to catch up with an older male sibling, things were very different for Marcel.

He continued to be beset by mysterious terrors. The fear that someone would pull his hair continued even after his curls had disappeared. He was plagued by recurrent nightmares. Often he would wake up at night and bury his head under the covers to protect himself. What for other children was a simple visit to the barber became, as he later described it, as dramatic as the earth “before or after the fall of Chronos.” His hair was cut short, but his dreams always threatened to take him back “into an annihilated world where he lived in fear of having his curls yanked.” That fear was tied to the fear of the dark, of solitude, of abandonment—nighttime feelings that made going to sleep the most painful part of his day. At night, Marcel sank into primordial anguish. “But his childhood struggled desperately at the bottom of a well of wretchedness from which nothing could release him,” he wrote of his character Jean Santeuil, adding that the pains of childhood are the worst of all because we don’t understand their causes. This sadness “inseparable from himself” didn’t prevent him from experiencing joy. But it explains his constant need for his mother, the only person capable of helping him deal with that anguish.

Jeanne at first tried to reassure her emotional child, showering him with affection, kisses, and comforting words. When he was sick, she stayed at his bedside and read to him for hours. Her voice calmed him, and he could fall asleep peacefully in her presence. But the child wasn’t sick all the time, and there was a little brother who also wanted Mama’s attention; Marcel was growing up and needed to be “reasonable.”

When I was still a child, no other character in sacred history seemed to me to have such a wretched fate as Noah, because of the flood which kept him trapped in the ark for forty days. Later on, I was often ill, and for days on end I too was forced to stay in the “ark.” Then I realized that Noah was never able to see the world so clearly as from the ark, despite its being closed and the fact that it was night on earth. When my convalescence began, my mother, who had not left me, and would even, at night-time, remain by my side, “opened the window of the ark,” and went out. But, like the dove, “she came back in the evening.” Then I was altogether cured, and like the dove “she returned not again.” I had to start to live once more, to turn away from myself, to listen to words harder than those my mother spoke; what was more, even her words, perpetually gentle until then, were no longer the same.

Although this passage from Marcel Proust’s first book, Pleasures and Days, probably refers to a somewhat later period in his childhood, it gives us a good overall sense of the relationship between Jeanne and her son, his efforts at separation and periods of regression, and his return to the curved hull of the ark, a magical maternal universe unto itself, drifting in the perpetual night of the unconscious.

Jeanne realized that her son’s demands were becoming more and more difficult to satisfy. Giving in wasn’t doing him any good. There was something excessive about his fits of tears, about his fervent kisses and the way he stayed glued to her—she saw this clearly. Nathé, whose principles were strict, criticized her weakness. Adrien accused her of turning Marcel into a girl. He’s a boy, for God’s sake! “We don’t want to mollycoddle him [. . .]. My husband and I are so anxious that he should grow up to be a manly little fellow,” says Madame Santeuil. Something about her use of “we” doesn’t ring true. What’s more, on the very next page of Jean Santeuil, she renounces those principles.

They had to be tougher, stricter with schedules, and had to stop putting up with Marcel’s flights of fancy, Dr. Proust believed. But bringing up children was a woman’s job. Adrien Proust wanted tranquillity when he got home from work. He involved himself with his sons only incidentally, in crises or when his peace of mind was threatened. Like many fathers, no doubt, he saw only a small part of things because he was rarely at home, and when he was there, his wife avoided tiring him with household details.

It was up to Jeanne to educate Marcel in the literal sense: to “lead him out” of this well of wretchedness, out of his frantic dependence. How could she not have been divided between her love for her child and the need to help him grow, to help him get through those time-honored stages that would make him a man? She believed that only willpower would allow him to overcome his own nervous disposition. They needed to develop his willpower. Take heart, little wolf, courage! But it also took all her strength not to give in to him, to resist the fits of weeping that tore at her heart, not to let herself be locked in a prison of passionate love. How should she set limits when he was asking for the fourth, fifth, or tenth time for a kiss she had already given him? When he clung to her just as she was leaving his room? When he squirmed on his bed and screamed so loudly that he was bound to wake his little brother, sleeping in the next room? When he stared at her with his big black eyes, so like hers? A part of her wanted to detach him from herself, and she knew she must; another part responded with all her strength to this swallowing up, and she drowned with him in this seamless love, continuing to nourish him from the umbilical chord that made her live according to his rhythms, made her watch over him, guide him, direct him.

We can’t understand Jeanne unless we recognize an ambivalence that she would never entirely master. Mother and son were united by a complex bond that the years would only tighten, making any separation impossible. Jeanne’s life was a long struggle to put a little distance between herself and her son, to render him capable of living without her—yet she was unable to detach herself, anxiety being the very ground of her love for him. A few months after Jeanne’s death, Marcel wrote these revealing words to Maurice Barrès:

Our entire life has been but a preparation, hers to teach me how to manage without her when the time came for her to leave me, and so it has been ever since childhood, when she refused to come back over and over again to say goodnight to me before going out for the evening, when she left me in the country and I watched the train take her away, and, later on, at Fontainebleau, and even this summer when she went to Saint-Cloud, I would find any excuse to telephone her—at all hours of the day. Those fears, which could be defused by a few words spoken over the telephone, or by her visiting Paris, or by a kiss, how powerfully they afflict me now when I know that nothing can ever allay them. And for my part, I often tried to persuade her that I could live quite well without her.

“Our entire life,” wrote Marcel. How could he have said it better? This “training” started in his childhood and didn’t stop until Jeanne’s death. She died with this worry, believing him even more vulnerable, even less able to cope with life, than he actually was. In the same letter, Marcel, in response to a remark by Barrès, denied being the person his mother loved best: “It was my father, though she loved me infinitely all the same.” It would be a mistake not to take these words literally. They set out admirably the terms of what must have been his mother’s dilemma (and his own, of course): “But while I wasn’t in the strict sense the person she loved best, and the idea of having a preference among her duties would have made her feel guilty, and it would have hurt her to see me draw inferences where she didn’t want them, she did love me a hundred times too much.”

All the elements of what must have been Jeanne’s dilemma are here: a woman caught between her duties as a wife and as a mother. But is “duty” the right word? Wouldn’t it be more accurate simply to say “love”? Jeanne Proust: a hostage to love, caught between a son who was too demanding and a husband who didn’t demand enough.

Sleep was the moment where the impossible separation was most intense. On five different occasions, Marcel Proust put words to the goodnight kiss. As time passed, he elaborated the scene, enriching it with notations, parentheses, metaphors, characters; it became ever more fictional, filled with a deep truth that the novelist gathered from the sources of memory. This truth didn’t lie in biographical details but in the essence of a lived experience, which he captured with increasing success. By juxtaposing these fictional transpositions, combining them, mixing them together, noting their differences and their similarities, we can approximate what must have been the mother’s perception and behavior, without losing sight of the fact that these texts reflect Marcel’s own vision, refracted by the act of creation. But this vision is crucial. It reveals the texture of a conflict that was as much the mother’s as the son’s. And in the story of this conflict, the most intriguing character may not be the one we expect.

When her sons were little, Jeanne, like many mothers, would go to their bedrooms and kiss them goodnight. The goodnight kiss, being tucked in, the candle blown out (or the light turned off) is a ritual for children throughout the world, including babies like Robert who fall asleep peacefully as soon as they close their eyes. For Marcel, the kiss was much more than a gesture of love or comfort. It was the life force that allowed him to face the evil powers of the night and overcome his fear of death, “the tender offering of cakes which the Greeks fastened about the necks of wives or friends, before laying them in the tomb, that they might accomplish without terror the subterranean journey and cross, without hungering, the Kingdom of the Shades.” He compared this kiss to the Communion wafer, as though it carried within it the sacred substance of the maternal body. Waiting for the kiss was proportionate to his anguish: incommensurable. Nothing could fill this bottomless well except the presence of his mother, a single, totalizing presence. On some evenings, all Jeanne had to do was bend down and kiss him, and he would calm down and fall asleep. She could then leave quietly and go back to her husband. But at other times she was so susceptible to the violence of her son’s need for her that she had to tear herself away from him. To leave him was to abandon him. She tried to reason with him, to make him ashamed. In vain. There were no limits. And because she knew how he suffered in letting her go, she occasionally gave in and gave him another kiss before fleeing.

Even more heartrending were those evenings when guests came for dinner. The children would eat first and come to the table to say goodnight before going upstairs to bed at eight o’clock. Jeanne knew how important the goodnight kiss was for her older son. Sometimes, to have a little more time with his mother, Marcel asked for a walk around the garden before the arrival of the guests. He would follow the path leading to the monkey puzzle tree. Jeanne’s garden smock occasionally got caught on one of its branches. The child would tug on her arm, drag his feet, compel her to pull him along, so assiduously was he putting off the fateful moment when he would have to leave her. Adoringly, he would kiss her hand with its fragrance of soap.

But at other times, when the doorbell rang, Nathé, the grandfather, would grumble with “unconscious ferocity” that “the children look tired, they need to go up to bed.” Marcel was about to kiss his mother, but Adrien, backing up his father-in-law, would urge: “Yes, go on now, up to bed with you; you’ve already said goodnight to each other as it is; these demonstrations are ridiculous!” Jeanne said nothing. She let the children go, and went to greet her guest—in Jean Santeuil it was a physician, Dr. Surlande; in In Search of Lost Time it was Swann. She fulfilled her role as mistress of the house.

One night in July 1878, in Auteuil, surrounded by the scent of rose bushes, the family was eating at the garden table—lobster, salad, pistachio and coffee-flavored ice cream, and chocolate cookies. The butler passed around the finger bowls, then the coffee. The children were upstairs. From time to time, Jeanne looked up at Marcel’s window. His candle was out, so he must be asleep. But he couldn’t be. Her suspicion was well grounded. Soon the window lit up. And here we have two versions: first the one in Jean Santeuil, the simpler of the two, the one that frames the narrative. Then the story in Swann’s Way.

The child tries to convince Augustin to take a note to his mother. Augustin refuses to bother her. Madame Santeuil happens to be giving Dr. Surlande an outline of her educational theories and her plans for her son’s future—whatever he might become, let him not be a genius—when a little blond head appears: “Mama, I want you for a moment.” A moment! Madame Santeuil rises, excuses herself, and, despite the protests of her father, goes upstairs to her son, with her husband’s support: “If she doesn’t go up, he’ll never get to sleep and we’ll be a lot more disturbed in an hour’s time.” She kisses Jean, who calms down, but when she’s about to go downstairs to rejoin the company, he bursts into tears, in total despair. Annoyed, but resigned, the mother sits down at his bedside, abandoning her principles and any hope of seeing him master his emotional outbursts. Jean “doesn’t know what’s the matter with him, or what he wants,” she explains to Augustin. By relieving the child of responsibility for the state he’s in, she makes him incapable of overcoming his nervous condition. He has turned into a sickly child. She has lost. She knows it.

In the much more elaborate version in Swann’s Way, other elements come into play. Françoise, the maid, slips a message to Mama, who refuses to give in. “Tell him there’s no answer.” After dinner, coffee is served outdoors, in the moonlight. When Swann has left, the parents exchange a few words about the dinner. The wife isn’t sleepy; the husband goes upstairs to undress. She stays downstairs, bides her time, pushes open the green lattice door that leads from the vestibule to the staircase, asks Françoise to help her unhook her bodice. Then she walks upstairs toward the master bedroom, candle in hand. She has scarcely reached the landing when an apparition throws itself upon her, a little boy who will be seven in two days, not quite the age of reason. Her surprise gives way to anger. “Go to bed.” The dramatic tension reaches its climax when the father in turn appears at the stairwell, a quasi-Prudhommesque, quasi-biblical figure in his nightshirt and the pink and violet Indian cashmere shawl that he ties around his head to prevent neuralgia. Panic. Then comes the child’s attempt at manipulation: he virtually blackmails his mother so that she will follow him into his room. But she snaps at him: “Run, run!”

It’s the father who turns the situation on its head. Although he is supposed to be the tougher of the two, he now suggests that the mother go in with her son. She protests timidly, in the name of her principles. We can’t let him get into the habit. But the father goes even further: “There are two beds in his room; go tell Françoise to prepare the big one for you and sleep there with him tonight.” And he adds, as a parting shot: “Now then, goodnight, I’m not as high-strung as the two of you, I’m going to bed.” In using the plural, “the two of you,” he equates mother and son as fragile beings of the same type.

By introducing the father into the story, giving him a major role, Proust restores Adrien’s role in the relationship that united Marcel to his mother. If this scene represents the failure of the rite of passage that should have enabled him to go to sleep like a big boy—like a man?—it is because his father gave up on him, didn’t force him to surmount his fears. The father’s sudden indulgence is an abandonment or a sign of indifference. My mother and my grandmother, wrote Marcel, “loved me enough not to consent to spare me my suffering, they wanted to teach me to master it in order to reduce my nervous sensitivity and strengthen my will.”

We’re struck by the mother’s passivity, her docility. Torn between the desire to strengthen her son—a role that should have been the father’s—and submission to her husband’s will, she obeys her husband. Proust compares his father to “Abraham [telling] Sarah she must leave Isaac’s side.” There he confuses—perhaps deliberately—Sarah, the lawful wife, with Agar, the servant with whom the patriarch had a son, Ismael. This slip allows Proust to make his point: the father sends his wife to his son’s side, just as Abraham sent Agar into the desert with Ismael. By opening the door to Marcel’s room, the father closes his own: “Now then, goodnight, [. . .] I’m going to bed.”

This is why the scene seems to me to reveal the complexity of everything at play between Jeanne, Adrien, and their son, beyond the novel. Could it be that she was so much a mother because they were no longer fully husband and wife? The question is worth asking.

The narrator’s mother—let’s call her Jeanne—also gives in to her emotions as she tries to stop her son’s crying: “There now my little chick, my little canary, he’s going to make his mama as silly as himself if this continues. Look, since you’re not sleepy and your mama isn’t either, let’s not go on upsetting each other, let’s do something.” Clad in her blue-flowered bathrobe, she sits down at his bedside in the cretonne armchair, holding a book with a reddish cover: George Sand’s François le Champi, the story—and here we see Proust’s genius—of an incestuous love between a child and his adoptive mother. “Sometimes—though rarely—in my childhood I knew the feeling of rest without sorrow, of perfect calm. Never did I know it as on that night. I was so happy that I didn’t dare go to sleep,” Marcel would write many years later. Finally, he does fall asleep.

When he awakens, his mother’s bed is empty. Jeanne has risen quietly, leaving a little note on the table: “When my little wolf wakes up, he should dress quickly, Mama is waiting for him in the garden.” The sun is already high in the sky when the shutters are opened. Jeanne looks up and smiles. The rose bushes and the nasturtium are climbing all along the house up to the window of his room. The gardener is watering the sunflowers. It’s a beautiful summer day.

It’s generally agreed that the scene of the goodnight kiss crystallizes episodes that must have occurred over and over in different times and places. Significantly, Proust situates the scene just before the child reaches the age of seven. He never would reach the age of reason. Jeanne often read to her son at night. Continually defeated, she finally admitted that Marcel was not responsible for his nervous temperament. But she persisted in battling what she called his “lack of willpower.” She never gave up educating him. She knew that one day he’d have to go to sleep without her.

And Robert? Robert slept like an angel.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 69-77 of Madame Proust: A Biography by Evelyne Bloch-Dano, translated by Alice Kaplan, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2007 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Evelyne Bloch-Dano

Translated by Alice Kaplan

Madame Proust: A Biography

©2007, 272 pages, 26 halftones, 5 line drawings

Cloth $27.50 ISBN: 978-0-226-05642-5 (ISBN-10: 0-226-05642-2)

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Madame Proust.

See also:

- A catalog of books in biography

- A catalog of books in literary studies

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects