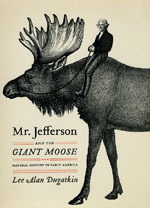

An excerpt from

Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose

Natural History in Early America

Lee Alan Dugatkin

A Moose More Precious Than You Can Imagine

Americans of the Revolutionary War era were understandably touchy about their standing compared with that of Europeans. It was one thing for the Europeans, particularly the French, to refer to Americans as upstarts, malcontents, and threats to the monarchy—in a sense many of them were all that. It was another matter entirely to suggest that all life forms in America were degenerate compared to those of the Old World. Yet that is precisely what Count Georges-Louis Leclerc Buffon, one of France’s most distinguished Enlightenment thinkers, and one of the best-known names in Europe at the time, claimed.

In his massive encyclopedia of natural history, Histoire Naturelle, Buffon laid out what came to be called the theory of degeneracy. He argued that, as a result of living in a cold and wet climate, all species found in America were weak and feeble. What’s more, any species imported into America for economic reasons would soon succumb to its new environment and produce lines of puny, feeble offspring. America, Buffon told his readers, is a land of swamps, where life putrefies and rots. And all of this from the pen of the preeminent natural historian of his century.

There was no escaping the pernicious effects of the American environment—not even for Native Americans. They too were degenerate. For Buffon, Indians were stupid, lazy savages. In a particularly emasculating swipe, he suggested that the genitalia of Indian males were small and withered—degenerate—for the very same reason that the people were stupid and lazy.

The environment and natural history had never before been used to make such sweeping claims, essentially damning an entire continent in the name of science. Buffon’s American degeneracy hypothesis was quickly adopted and expanded by men such as the Abbé Raynal and the Abbé de Pauw, who believed that Buffon’s theory did not go far enough. They went on to claim that the theory of degeneracy applied equally well to transplanted Europeans and their descendants in America. These ideas became mainstream enough that Raynal felt comfortable sponsoring a contest in France on whether the discovery of America had been beneficial or harmful to the human race.

Books on American degeneracy were popular, reproduced in multiple editions, and translated from French into a score of languages including German, Dutch, and English; they were the talk of the salons of Europe and the manor houses of America. And it wasn’t just the intelligentsia of the age who were paying attention—this topic was discussed in newspapers, journals, poems, and schoolbooks.

Thomas Jefferson understood the seriousness of Buffon’s accusations, and he would have none of it. He was convinced that the data Buffon and his supporters relied upon was flawed, and possibly even intentionally so. And Jefferson quickly realized the long-term consequences, should the theory of degeneracy take hold. Why would Europeans trade with America, or immigrate to the New World, if Buffon and his followers were correct? Indeed, some very powerful people were already employing the degeneracy argument to stop immigration to America. What’s more, this insipid theory challenged the entire premise of the American Revolution: that man could rise to any heights for which he worked.

Jefferson led a full-scale assault against Buffon’s theory of degeneracy to insure that these things wouldn’t happen. He devoted the largest section of the only book he ever wrote—Notes on the State of Virginia—to systematically debunking Buffon’s degeneracy theory, taking special pride in defending American Indians from such pernicious claims. The author of the Declaration of Independence employed more than his rhetorical skills in Notes. Jefferson produced table after table of data that he had compiled, supporting his contentions. Parts of Jefferson’s book were reprinted in dozens of newspapers across the United States in the 1780s. Even a hundred years after that, one Jefferson scholar called Notes on the State of Virginia arguably the most frequently reprinted Southern book ever produced in the United States to that time.

As minister to France, Jefferson knew Buffon, and even dined with him on occasion. He was confident that the Count was a reasonable, enlightened man, who would retract his degeneracy theory if he were presented with overwhelming evidence against it. Notes on the State of Virginia was just one weapon in Jefferson’s arsenal. Jefferson also wanted to present Buffon with tangible evidence—something the Count could touch. He tried with the skin of a panther, and then the bones of a hulking mastodon that had roamed America in the distant past, but Buffon didn’t budge. Jefferson’s most concerted effort in terms of hands-on evidence was to procure a very large, dead, stuffed American moose—antlers and all—to hand Buffon personally, in effect saying “see.” This moose became a symbol for Jefferson—a symbol of the quashing of European arrogance in the form of degeneracy.

Jefferson went to extraordinary lengths to obtain this giant moose. Both while he was being chased from Monticello by the British in the early 1780s, and then later while he was in France drumming up support and money for the revolutionary cause in the mid-to-late 1780s, Jefferson spent an inordinate amount of time imploring his friends to send him a stuffed, very large moose. In the midst of correspondences with James Monroe, George Washington, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin over urgent matters of state, Jefferson found the time to repeatedly write his colleagues—particularly those who liked to hunt—all but begging them to send him a moose that he could use to counter Buffon’s ideas on degeneracy. Consider the following letter to former Revolutionary War general and ex-governor of New Hampshire, John Sullivan:

The readiness with which you undertook to endeavor to get for me the skin, the skeleton and the horns of the moose … emboldens me to renew my application to you for those objects, which would be an acquisition here, more precious than you can imagine. Could I chuse the manner of preparing them, it should be to leave the hoof on, to leave the bones of the legs and of the thighs if possible in the skin, and to leave also the bones of the head in the skin with horns on, so that by sewing up the neck and belly of the skin, we should have the true form and size of the animal. However, I know they are too rare to be obtained so perfect; therefore I will pray you send me the skin, skeleton and horns just as you can get them, but most especially those of the moose. Address them to me, to the care of the American Consul of the port in France to which they come.

The hunt for this moose, and the attempt to get it shipped to Jefferson, and then Buffon in Paris, is the stuff of movies. The plotline involved teams of twenty men hauling a giant dead moose through miles of snow and frozen forests, a carcass falling apart in transit, antlers that didn’t quite belong to the body of the moose but could be “fixed on at pleasure,” crates lost in transit, irresponsible shippers, and a despondent Jefferson thinking all hope of receiving this critical piece of evidence was lost. Eventually, though, the seven-foot-tall stuffed moose made it to Jefferson, and then to Buffon.

Because he saw so much on the line, Jefferson, as was his way, obsessed over providing every relevant fact to counter Buffon’s anti-American theory of degeneracy; and his overall counterattack, including the moose, was powerful. At his 1826 funeral, one orator referred to Jefferson’s efforts in this regard as the equivalent of leading a second American revolution. Thanks to Jefferson, refuting the theory of degeneracy was such a point of pride for early citizens of the United States that it was discussed in the opening pages of the country’s first school textbooks.

Yet, despite Jefferson’s passionate refutation, the theory of degeneracy far outlived Buffon and Jefferson; indeed, it seemed to have a life of its own. It continued to have scientific, economic, and political implications, but also began to work its way into literature and philosophy. On one side were those who continued to promulgate degeneracy—people such as the philosopher Immanuel Kant and the British poet John Keats, who described America as the single place where “great unerring Nature once seems wrong.” On the other side was a cadre that included Lord Byron, who spoke of America as “one great clime,” Washington Irving, who mocked Buffon’s theory in The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, and Henry David Thoreau, who used his essay “Walking” as a platform “to set against Buffon’s account of this part of the world and its productions.” This group saw America as a vast, almost unlimited land of resources, a place where nature shines on a world of healthy, hardworking people: and they labored (quite successfully) to make this idea part of our national identity. All of this can be traced back to the degeneracy argument between Buffon and Jefferson, and, to some extent to Jefferson’s moose itself.

Eventually the degeneracy argument died; but it did not die an easy death …

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages ix–xii of Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose: Natural History in Early America by Lee Alan Dugatkin, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2009 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Lee Alan Dugatkin

Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose: Natural History in Early America

©2009, 184 pages, 25 halftones

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose.

See also:

- Our catalog of books in the history and philosophy of science

- Our catalog of books in biology

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog