Mapping Virtue and Vice

Mapping the City of Virtue

|

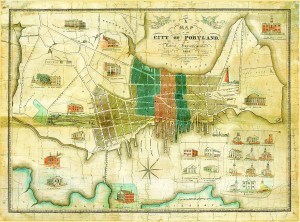

John Cullum, "A Map of the City of Portland with the Latest Improvements" (1836). Osher Map Library, University of Southern Maine.

|

That city maps and views present particularized and idealized images of unique places can be seen by comparing different approaches taken for representing U.S. cities in the nineteenth century. City maps and views allowed the wealthier residents who bought them to share a common image of a single, unified, economically active, and civic-minded community. It was in that spirit that John Cullum prepared, engraved, and printed a map of Portland, Maine, in 1836. Portland was still a “walking city” at the time, but one that had doubled in size in the fifty years since the American Revolution. It had grown all the way across the neck of land from its original site as a port town along the Fore River, and was now beginning to climb up the bounding Mount Joy (Munjoy) and Bramhall hills. Cullum bracketed the map’s title with two angels, who blow trumpets and bear laurel wreaths, literally heralding Portland’s dynamic economy and growth. He selected certain buildings to be shown in architectural profile—the customhouse, city hall, courthouse, exchange, large hotels, and more than fifteen churches and meetinghouses—to highlight the cityÆs economic vitality, civic structure, and morality. The area of the built city was further divided into wards, indicating the presence of local democratic institutions and city government. All in all, this map presented a comprehensive and positive view of Portland to its inhabitants; it depicted a dynamic, moral, and socially coherent community.

Mapping the City of Vice

|

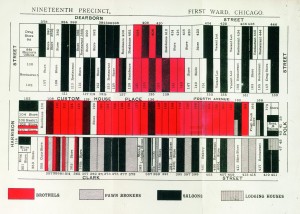

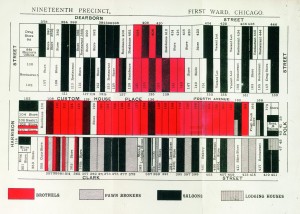

"Nineteenth Precinct, First Ward, Chicago." From William T. Stead, If Christ Came to Chicago! (1894). Newberry Library.

|

In contrast with this “view from above” are many “views from below,” which were made for the same wealthier audiences as the city maps and views, but which depicted particular aspects of urban life. These partial views focused on the underside of the modern industrial city, specifically its less desirable structures (slums, taverns, gin mills, and brothels) and inhabitants (laborers, immigrants, criminals, moral deviants, and the diseased). They took the form of illustrated urban ethnographies, dictionaries of cant, exposés of poor sanitation and disease, and, occasionally, maps of especially noisome neighborhoods. One such map images a particular site of vice and iniquity in Chicago. It highlights specific sites of immoral or illegal activity: lodging houses, which accommodated a transient and unregulated population that was a source of great anxiety for the city’s more sedate and decorous populace; pawnbrokers, who were both a source of quick cash and a ready home for stolen goods; saloons, which were intrinsically nefarious at a time when the temperance movement was strong among the sober middle classes; and brothels, which naturally were sites of moral depravity and turpitude. The map labels but does not emphasize the more morally neutral economic activities of the legitimate stores and restaurants. Thus, while the views from above gave their consumers—members of the cityÆs upper and middle classes—a reassuring image of the economic vitality, morality, and communal wholeness of their hometowns, the views from below worked to tame the anxieties about social dysfunction held by the same people, by isolating each dysfunction, comprehending it, and so enabling it to be corrected and eliminated.