An interview with

Neil Harris

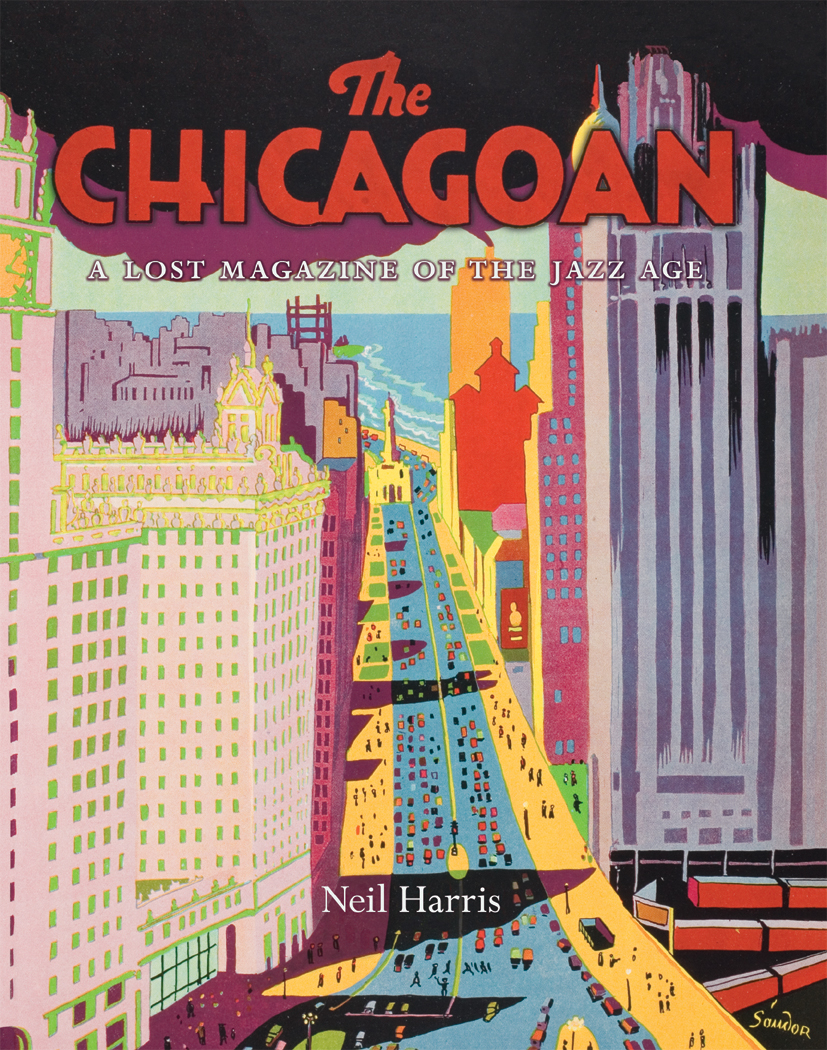

author of The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age

Question: The Chicagoan first appeared in June 1926. Can you set the context for us? What was Chicago like in the mid-1920s?

Answer: The image of Chicago that was forged in the 1920s would last for decades. It is still quite familiar. Chicago was “stormy, husky, and brawling,” as Carl Sandburg once wrote. It was also at the peak of its economic power—the stockyards butchered twenty million animals annually; millions of bushels of grain were milled, stored, and moved through the city; stench from the stockyards and smoke from the steel mills and oil refineries hung in the air. The population grew by about 25% in the 1920s, an increase of 680,000 people. New apartment buildings and bungalows collared the city.

The skyscraper was born in Chicago and by the ’20s the city had plenty of them. It also had an opulent opera house, the world’s largest fountain, the world’s largest building, and the world’s largest hotel. Fine museums and great universities were established. But Chicago was also notable for its slums and squalor, its violent labor and racial conflicts.

Of course, this was the era of Prohibition and Chicago’s most famous resident—the world’s greatest gangster—was Al Capone. Chicago was the capital of racketeering and vice and, under the leadership of political boss and mayor William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, the city administration was flamboyantly corrupt.

So despite dashes of culture, Chicago was widely perceived as a place of raw commerce and crime—brawny, philistine, vulgar, and violent.

Question: The Chicagoan arrived on the scene a little more than a year after the first issue of the New Yorker. Was that magazine the model for the Chicagoan?

Answer: Of course. From layout to covers, the magazine was created as a direct imitation of the New Yorker. The New Yorker began to achieve considerable influence in the late 1920s and 1930s, reaching readers far beyond the metropolis. Creators of the Chicagoan hoped to do something of the same. In 1931 the format of the Chicagoan changed; it became larger, and seemed more like some other magazines, combining features of Town and Country, Vanity Fair, and perhaps some others.

The Chicagoan began as an effort to counter the city’s negative reputation. It offered a snapshot of Chicago’s artistic and literary life in the 1920s and 1930s. It was selective, for this was an elitist lifestyle magazine advising a wealthy audience on how to consume. As such, it reveals what some Chicagoans thought was interesting or important. Thus it helps capture one sensibility of that time, although of course there were others. The magazine is significant also because it features artists, critics, and writers who have, for the most part, been lost to history.

Question: How about the literary community of Chicago in the 1920s? What writers and journalists could the Chicagoan draw on and/or celebrate?

Answer: Unfortunately, Chicago’s literary renaissance of the 1910s was over. The writers it produced—Sherwood Anderson, Floyd Dell, Theodore Dreiser, Ring Lardner, Edgar Lee Masters, Carl Sandburg, Ben Hecht, George Ade, Vachel Lindsay, and Robert Herrick—had almost all left town, going east to New York or west to Hollywood. Writers such as James T. Farrell, Richard Wright, and Nelson Algren were not yet on the scene.

Chicago newspapers, however, continued to thrive in the 1920s. Tough-talking editors and cynical reporters—of the sort made famous in Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s Broadway hit of 1928, The Front Page—inhabited the newsrooms of the half-dozen English language dailies. The Chicagoan was a journalistic magazine—a vehicle for criticism, gossip, wisdom, and wit.

Question: Even the briefest glance at the book makes it abundantly clear that the most distinctive feature of the Chicagoan was its art—not only the bold covers, but a multitude of interior illustrations, cartoons, and caricatures. Was this another case of following in the footsteps of the New Yorker or are their aspects of the art of the Chicagoan that are distinctively Chicago?

Answer: The artists, in particular, seem to me to have been very talented. The book I have written contains a biographical index featuring about 100 contributors. It was difficult to find out very much about quite a few of them. There exists, so far as I know, no archive documenting the Chicagoan so there is no evidence suggesting how the magazine operated on a daily basis. I reconstructed its history as best I could.

Quite a number of the artists working for it were graduates or students of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and/or the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, both training grounds for the highly active artist community in Chicago, which thrived on commercial work from printers, advertising firms, mail-order houses, department stores, and manufacturers. The 1920s also saw the flowering of artistic movements and organizations that challenged orthodox aesthetics; for example, Loop department stores hosted exhibitions for artists rejected by the Art Institute’s annual shows.

Much of the art of the Chicagoan was in the New Yorker spirit, but of course the themes were specifically Chicagoan—many of the covers presented Chicago buildings and landscapes, or occasionally events, like the Dempsey-Tunney fight. There was a lot of local nostalgia, but then the New Yorker, in its early days, also featured a lot of local history and chest thumping. The page design was, at certain moments, more dramatic than the New Yorker typically was.

Question: The Chicagoan disappeared from newstands with its last issue of April 1935. And then it disappeared from historical memory until now. How did you uncover the existence of the magazine?

Answer: The Chicagoan survived for nine years, from 1926 to 1935, which in the magazine world was not a bad run. At its peak it reached some 23,000. Few people outside of Chicago knew anything about it. I found hardly any mentions in the national press; Time did run an article about a change in its format, but there was little else.

I encountered the magazine accidentally while browsing the stacks at the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library. The nine bound volumes bearing the title were plain on the outside, but I was astonished by what I found inside, particularly by the covers. I hope readers of this book will find them as striking as I did.

Its obscurity is one reason why I found it so fascinating. The book is designed to re-introduce this group of largely forgotten artists and writers. With support from the Driehaus Foundation in Chicago, and the Furthermore Foundation in New York, we were able to produce a large, well printed book, with 81 color plates featuring the covers. I wrote a detailed contextual introduction. My wife, Teri Edelstein, worked with me throughout the project, and helped me choose what we hope is a representative sampling. This was the first time I had ever worked on this kind of anthology; selecting the final choices was a complicated process. But the possibility of bringing these voices back to life seemed important. I hope the book will stimulate others to discover more about the artists. There is more to be learned, but I thought it important to bring out what I had uncovered so far, although there remains much more to know. ![]()

Copyright notice: ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press.

Neil Harris

With the assistance of Teri J. Edelstein

The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age

©2008, 400 pages, 81 color plates, 301 halftones 11×14

Cloth $65.00 ISBN: 9780226317618

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for The Chicagoan.

See also:

- A gallery of covers and illustrations from the Chicagoan

- Sample pages in PDF (7mb) from the book

- Our catalog of books about Chicago

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog